Ocular emergencies in the South Asia region

Related content

Eye care providers at different levels in South Asia must be able to diagnose, manage, initiate first-aid and refer during an ocular emergency.

Ocular emergencies are an important cause of morbidity in South Asia and studying their spectrum and presentation is vital for developing local preventive and therapeutic programmes. Primary care providers must be able to diagnose, manage, initiate first-aid, or refer, as any delay in treatment during an ocular emergency can result in permanent loss of vision. 1

Ocular trauma

Any form of trauma is an emergency and prompt treatment can arrest complications and long-term morbidity (Figure 1).

The prognosis of any injury is commonly made worse by delayed presentation and use of inappropriate, untested products and traditional medicines.2 Health promotion interventions in injury prevention include raising awareness and actively involving the community. Workplace trauma can be prevented through occupational health laws which educate workers and promote the use of protective eyewear. Children are often victims of ocular trauma, so health education in schools is very important.

Ocular trauma can be classified into

- Penetrating injuries

- Blunt injuries

- Chemical injuries

- Ocular burns

Penetrating injuries

Open globe injuries are caused by sharp objects in which there is full thickness wound in the eyewall. The patient may present with a sudden loss of vision, pain, watering and an inability to open the eye. Visual acuity should be measured for each patient. Surgical closure is necessary in case of open globe injuries in order to minimise the risk of further infection. Intra-ocular foreign bodies, if present, should be removed; this requires specialist facilities and surgery.

Blunt injuries

Closed-globe injuries are caused by blunt objects, where there is no full thickness wound of the eyewall comprising sclera and cornea.

The patient may present with loss of vision, pain and inability to open the eye. Visual acuity, pupillary reactions and the posterior segment should be evaluated in all cases. The management will depend on the severity of the injury. With conservative treatment, a simple hyphema will usually reabsorb after a few days.

Chemical injuries

Chemical injuries may present in different ways, depending on the nature of the chemical agent, its concentration and volume, and the duration of exposure.3 Both acids and alkalis can cause eye injuries. Many occur in men who are at risk of exposure to chemicals such as lime (calcium hydroxide), ammonia, sodium or magnesium hydroxide in the workplace (Figure 2).

The first step in the management of chemical injuries is immediate and meticulous irrigation of the eye. This is done by everting the eyelids and flushing with ringer lactate or normal saline until the pH of the ocular surface is neutralised. Timely treatment that includes topical antibiotics, cycloplegics, topical steroids, topical sodium ascorbate & citrate 10%, oral doxycycline, oral ascorbate and tear substitutes must be instituted.

Ocular burns

Ocular damage from thermal burns can result from contact with boiling liquid, molten metal, flames, gasoline explosions, steam or hot tar. Firecrackers can cause combined chemical and thermal burns on the ocular surface.

The management of ocular burns depends on the type of injury. However immediate cleaning and irrigation with normal saline or clean water is an important first aid measure.

Corneal Ulcer

Corneal ulcers are common in the South Asian region, especially in countries with rural and developing economies.4 A corneal ulcer is defined as a corneal epithelial defect with infiltration of the deeper stroma, most commonly caused by infection. Viral ulcers arise spontaneously on a previously intact epithelium, while bacterial and fungal ulcers occur after a traumatic break in the corneal epithelium. Fungal ulcers typically start after an injury with organic matter.

Patients with a corneal ulcer present with pain in the eyes, foreign body sensation, photophobia, discharge, watering and blurred vision. It is important to elicit a proper history and sequence of events. Patients should be asked about ocular medications, especially the use of corticosteroids, previous eye surgery, ocular disease and systemic illness.

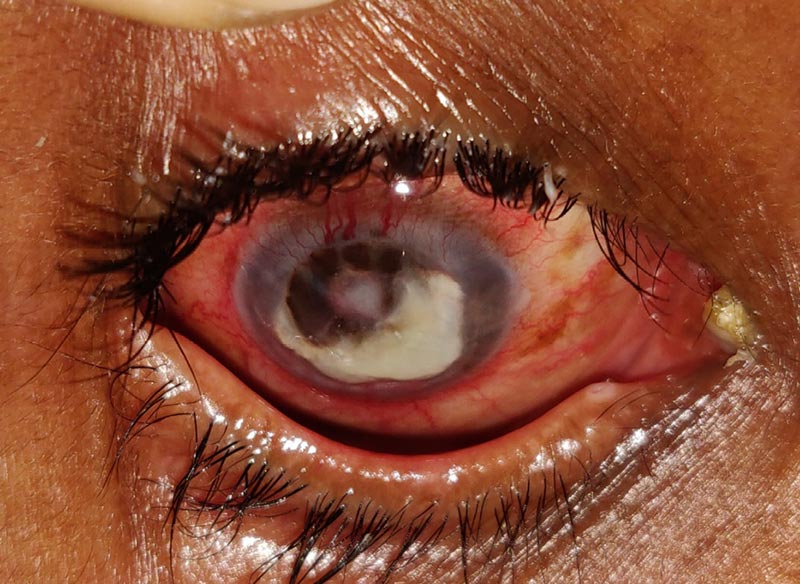

On examination, the eye will typically look congested with a white corneal lesion indicating stromal infiltration (Figure 3). A corneal scraping can be taken and sent for Gram and KOH staining along with bacterial and fungal culture and sensitivities, since determining the infectious aetiology is important to guide future treatment.

Immediate initiation of a topical antibiotic followed by prompt referral to a higher centre is necessary. Fortified antibiotics such as tobramycin and a cephalosporin or vancomycin are appropriate for severe, deep, or central corneal ulcers. Fungal ulcers are treated with topical natamycin 5% or topical voriconazole 1% eyedrops. Supportive treatment like cycloplegics, oral analgesics and antiglaucoma agents maybe required. Close follow-up is essential for all corneal ulcers as non-resolving ulcers or penetrating ulcers (Figure 4) may require an urgent therapeutic keratoplasty to debulk the cornea of infectious tissue and/or restore the integrity of the eye (Figure 5).

Prevention

Agricultural workers can use protective goggles that can aid in prevention of corneal ulcers. Community awareness of risk factors and effects of using traditional medicine can help in minimising severe consequences. Early recognition of symptoms, institution of appropriate treatment by the community health workers or ophthalmologists and prompt referral where necessary are critical in prevention of corneal ulcers.

Acute glaucoma

Acute angle-closure glaucoma is caused by the sudden closure of the anterior chamber angle. This leads to inadequate drainage of the aqueous humour and a subsequent elevation in intraocular pressure (IOP) which can lead to optic nerve damage. It is more common in the South East Asia region and if not recognised and treated on time can cause blindness within hours.

Patients present with severe ocular pain, decreased vision, nausea and vomiting, intermittent blurring of vision with halos, and headache. Ocular examination shows conjunctival infection, corneal oedema, a mid-dilated pupil that does not react well to light, shallow anterior chamber and decreased vision. IOP usually ranges from 40 to 90 mm Hg.

Once acute angle closure is suspected, IOP is lowered with oral acetazolamide and topical timolol, pilocarpine, and apraclonidine, while monitoring changes to the angle and optic nerve head. Hyperosmotic agents such as oral glycerol or intravenous mannitol are effective in lowering IOP during an emergency. Once IOP is controlled laser iridotomy is performed in both the affected eye and the fellow eye as well to prevent acute attacks. Prompt, appropriate diagnosis, aggressive treatment and management are necessary to prevent, or minimise, significant ocular morbidity in patients with angle closure glaucoma.

Acute loss of vision

Acute loss of vision in a white eye can occur due to central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO), retinal detachment, optic neuritis (Table 1). Immediate evaluation and referral to a tertiary care centre is important. Risk factors for CRAO include old age, being male, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and coagulopathies. Control of modifiable risk factors via health education and health promotion is the primary prevention of CRAO.

| Eye emergency | Care at different levels |

|---|---|

| Penetrating injury | Primary level

|

Secondary level

|

|

Tertiary level

|

|

| Chemical injury | Primary level

|

Secondary level

|

|

Tertiary level

|

|

| Corneal ulcer | Primary level

|

Secondary level

Refer to a tertiary ophthalmic centre if:

|

|

Tertiary level

SURGICAL OPTIONS

|

|

Endophthalmitis

|

Primary level

|

Secondary level

|

|

Tertiary level

|

|

Orbital cellulitis

|

Primary level

|

Secondary level

|

|

Tertiary level

|

|

Acute glaucoma

|

Primary level

|

Secondary level

|

|

Tertiary level

|

|

Optic neuritis

|

Primary level

|

Secondary level

|

|

Tertiary level

|

|

Retinal detachment

|

Primary level

|

Secondary level

|

|

Tertiary level

|

References

1 Girard B, Bourcier F,Agdabede I,Laroche L. Activity and epidemiology in an ophthalmological emergency center. J Fr Ophtalmol 2002;25:701-11.

2 Epidemiological patterns of ocular trauma. Aust NZ J Ophthalmol.1992 May;20(2):95-8.

3 Khathutshelo Mashige. Chemical and thermal ocular burns: a review of causes, clinical features and management protocol, South African Family Practice 2016, 58:1, 1-4

4 Garg P, Rao GN. Corneal ulcer: diagnosis and management.Community Eye Health. 1999;12(30):21-23